Saturday, September 27, 2014

Friday, September 26, 2014

Monday, September 15, 2014

Friday, September 12, 2014

Kutiman - Thru You Too - GIVE IT UP

"Kutiman" harvests bits and pieces from random YouTube videos from

all over the interwebs and sews them together into cohesive, artful

and lush aural landscapes.

This one is a favorite

This one is a favorite

Enjoy...

Friday, September 5, 2014

In General I Don't Believe In Marriage, But...

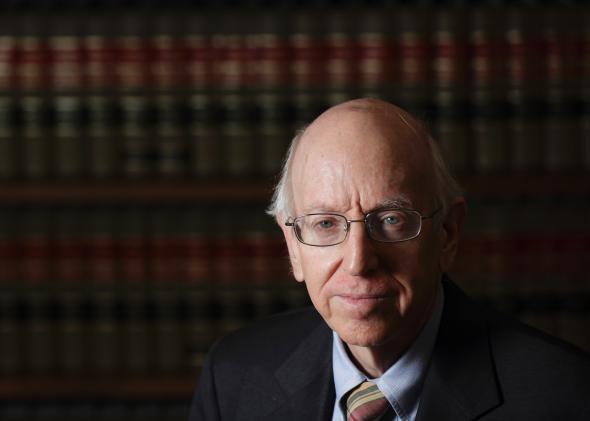

... Judge Posner’s Gay Marriage Opinion Is a Witty, Deeply Moral Masterpiece

By Mark Joseph Stern

Photo by John Gress/Reuters

Last May, after the proudly independent U.S. District Judge John E. Jones III struck down Pennsylvania’s gay marriage ban, I wrote

that the many judges slaying such bans seemed to be in subtle

competition to write the one marriage equality opinion that history will

remember. Since then, that competition has only grown fiercer, as an

expanding roster of judges reaches new heights of eloquence and reason

in their pro-equality opinions.

But Thursday’s ruling by 7th Circuit Judge Richard Posner,

which struck down Indiana’s and Wisconsin’s gay marriage bans, is a

different beast altogether. In his opinion,

Posner does not sound like a man aiming to have his words etched in the

history books or praised by future generations. Rather, he sounds like a

man who has listened to all the arguments against gay marriage,

analyzed them cautiously and thoroughly, and found himself absolutely

disgusted by their sophistry and rank bigotry. The opinion is a

masterpiece of wit and logic that doesn’t call attention to—indeed,

doesn’t seem to care about—its own brilliance. Posner is not writing for

Justice Anthony Kennedy, or for judges of the future, or even for gay

people of the present. He is writing, very clearly, for himself.

Ironically, by writing an opinion so fixated on the facts at hand,

Posner may have actually written the one gay marriage ruling that the

Supreme Court takes to heart. Other, more legacy-minded judges

have attempted to sketch out a revised framework for constitutional

marriage equality, granting gay people heightened judicial scrutiny and declaring marriage a fundamental right.

But Posner isn’t interested in making new law: The statutes before him

are so irrational, so senseless and unreasonable, that they’re noxious

to the U.S. Constitution under almost any interpretation of the equal protection clause.

Posner’s opinion largely follows the points he made during his forceful, trenchant, deeply empathetic questioning

at oral arguments. To his mind, there’s no question that gays

constitute a “suspect class”—that is, a group of people with an

immutable characteristic who have historically faced discrimination.

Refreshingly, Posner performs a review of “the leading scientific

theories” about homosexuality to illustrate that being gay isn’t a

choice. (Compare this with Justice Antonin Scalia’s gay rights dissents,

in which he suggests that there’s no such thing as a gay orientation at

all and that “gay” people are just disturbed individuals performing

debauched sex acts.)

This review is actually unnecessary, since both Indiana and Wisconsin

conceded that gay people are born that way. But it serves to reinforce

Posner’s analytical framework—basically, that a state can’t disadvantage

a suspect class of people without a rational basis. Note that low bar:

Not a compelling interest, or even a substantial one. If the states

could only prove a rational interest in excluding gay people from marriage, their laws would pass constitutional muster.

And what are the states’ allegedly rational bases? At oral argument,

the states repeatedly pressed the “responsible procreation” argument.

Here’s Posner’s (quite accurate) summary of that defense:

[The] government thinks that straight couples tend to be sexually irresponsible, producing unwanted children by the carload, and so must be pressured (in the form of government encouragement of marriage through a combination of sticks and carrots) to marry, but that gay couples, unable as they are to produce children wanted or unwanted, are model parents—model citizens really—so have no need for marriage.

And here’s his own take on the argument:

Heterosexuals get drunk and pregnant, producing unwanted children; their reward is to be allowed to marry. Homosexual couples do not produce unwanted children; their reward is to be denied the right to marry. Go figure.

This is all very amusing. But Posner has a serious moral and legal

point to make. The states’ arguments against gay marriage aren’t just

irrational: They’re insulting, degrading, and downright cruel to the

adopted children of gay couples. Posner describes this case as being,

“at a deeper level,” about “the welfare of American children.” Two

hundred thousand children are being raised by gay couples in America,

including several thousand in Indiana and Wisconsin. Both states admit

that children benefit psychologically and economically from having

married parents. These facts would seem to suggest a compelling interest

in support of gay marriage, since banning it actively, demonstrably harms children.

At oral argument, Posner pressed this point—one Justice Kennedy has made as well—and the state was unable to muster an intelligible retort.

He also asked whether the states cared at all that their laws harmed children. Their answer: Not really.

Posner acknowledges that a law that harms a suspect class (and their

children) might still be rational if it has “offsetting benefits.” But

who could gay marriage bans possibly benefit? Once again, Posner asked

this question at oral argument and received an evasive response.

It’s clear from his opinion that Posner has rifled through the

states’ extensive briefs to find an answer to this question—and come up

short. There is simply no harm, Posner writes, “tangible, secular,

material—physical or financial, or … focused and direct” done to anybody by

permitting gay marriage. Conservative Christians may be offended, but

“there is no way they are going to be hurt by it in a way that the law

would take cognizance of.” A lot of people, after all, objected to

interracial marriage in 1967—but that didn’t stop the court from

invalidating anti-miscegenation laws in Loving v. Virginia.

In his opinion, Posner makes these points with trenchant humor. But

beneath his droll wit lies a moral seriousness that gay marriage

opponents, even those on the high court, will be unable to shrug off.

The modern arguments against gay marriage may be breathtakingly silly—but

by mocking them, we ignore the profound harms that marriage bans

inflict on gay people and their families. By placing these families at

the center of his analysis, Posner restores the equal protection clause

to its rightful place as the safeguard for all whom the state seeks to

harm unjustly. His message for those who hope to demean gay people and

their children is clear: Not on my watch.

Mark Joseph Stern

Mark Joseph Stern is a writer for Slate. He covers science, the law, and LGBTQ issues.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)